Lord Rabbi Jonathan Sacks writes about a medical examination where he was put on a brisk-paced treadmill. “What I am testing” the doctor explained, “is how long it takes when you come off the treadmill, for your pulse to return to normal.” Rabbi Sacks concluded that the measure of health is in one’s power of recovery. This applies not just to individuals, but to peoples and their leaders.

My friend Fred, an aboriginal man in his thirties, was borderline retarded. It’s unclear which side of the line he was on. I don’t know if he was born that way, or if he damaged his brain with drugs. Maybe it was the result of a beating by his stepfather. Fred had told me about his baby sister: how he tried to protect her when their stepfather attacked. The baby died, and Fred’s mother told the police that she fell and hit her head. She didn’t want to lose her new husband.

So Fred might have literally had his mind beat out of him. Anyways, the missionary in the little native community

arranged to send him to Connecticut, where he worked as a gardener and housekeeper for a wealthy family, and where the odds of getting beaten to death were much lower. Fred believed that the missionary saved his life.

When I met Fred he was working occasionally as a busboy in a restaurant. His main source of income was his career as a homosexual prostitute. He didn’t like being a prostitute, nor did he like being a homosexual, but he was both. He said he was jealous of me: straight, with a family. He wished he was straight.

I was working for a regional native organization, and Fred was from that region. So when he saw the chance of making a connection to his original home, he came to see me. I liked Fred, and we spent many hours talking. He was saving up for a trip home, to see his mother. His excitement grew over the months, as he described the little community he came from. He hoped to find his mother, who he hadn’t heard from since he moved away.

In the meantime, the entire Executive of the organization I worked for came to town; about four or five people. The President greeted Fred as one of her own. She took an interest in him, was kind to him. The rest of the Executive was not. Fred told me they were insulting and unpleasant, accusing him of abandoning his people, of being a turncoat. Fred was devastated.

He finally got together the money to travel home, to see his mother. He didn’t find her. He came across his stepfather, who asked him for money. When Fred refused, the stepfather angrily accused him of violating the Commandment of honoring your father and mother.

He didn’t find any friends, any family there. The best treatment he got was being ignored. The rest was far crueler. On his return, Fred told me he was finished with that place, with those people.

Original art by Esti Mayer

Some careers are associated with risks. Miners risk getting trapped underground. Physicians have double the suicide rate of the general population. Roofers fall. Homosexual prostitution is associated with AIDS, but Fred was shocked when he learned he was infected. He had no idea how it could happen to him (remember that he was borderline retarded). This was before there were effective treatments for the disease.

He was well enough after his initial diagnosis to be released from hospital, and went back to work; not as a busboy. I told him he couldn’t work as a hooker because he would infect his clients. Fred asked me to lend him money so he wouldn’t have to turn tricks. He needed “emergency money for the weekends.”

After a few loans, I asked him what the emergency money was for. Did he have food? Yes. Bus fare? Yes. So what was the money for? To go out to bars with friends. I stopped with the emergency loans. I couldn’t take responsibility for the well-being of Fred’s clients.

Fred was an aboriginal artist, but not a very good one. He hoped to make a career out of his art, so I bought one of his pencil drawings and hung it in my office. I told him I was very proud of it; one day it would be worth a lot of money. He was pleased, and started planning his next masterpiece.

I wouldn’t say that AIDS cut short Fred’s art career, but it did cut short his life. He died alone, uncared for; unnoticed by his family, by his long-ago community.

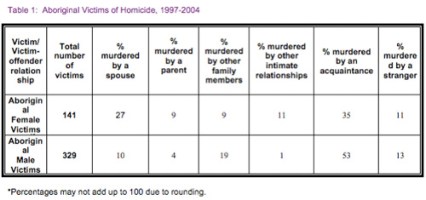

Fred had a lot of pain in his life. I wasn’t witness to most of it, but I did see how he was deeply hurt by the encounters with his people. When I hear native people screaming about their suffering at the hands of the society that engulfs them, I often think about Fred. Aboriginal people don’t have much control over what outsiders do, but what about the suffering so many native people inflict upon themselves? Rates of spousal assault against aboriginal women are more than three times higher than those against non-aboriginal women. There is more sexual assault, and more of it is committed by people within their own community. Pipeline construction and other resource development projects are trivial, in comparison to the harm aboriginal Canadians do to themselves.

Yes, many of them have had their minds messed up by the residential school system. Friends of mine told me about their experiences, which at first I refused to believe. Amos described how the Minister’s sister would inspect all the naked teenage boys after their showers. Robert actually smiled as he recalled the heavy stick hitting his back; punishment for speaking Cree. Another friend’s grandfather had a mousetrap closed on his tongue for the same offense.

The aboriginal people have suffered greatly. How many of them want to recover, want to move forward? And how many prefer to hang onto their victim-hood, using it as a pretext to excuse the suffering they inflict on themselves? This ratio is the measure of their societies, and the measure of their futures.

Fred was a druggie, a gay prostitute, a mediocre artist at best. He was a sensitive human being with a weak mind and a frayed heart. He did not deserve the pain inflicted on him by his family, by his people. His people do not deserve the pain they inflict upon themselves, but they choose it nonetheless.